On Saturday I went to the Balnarring Sustainability Fair to spread the word about sustainable farming, the organic “industry” and Community Supported Agriculture. From the historical inspirations for sustainable farmers, to the industrialisation of agriculture and how it has changed the food we eat, to the CSA movement and the community support necessary to have a local, ecologically, socially and economically sustainable food source, my head was swirling with data and I found it hard to sleep the night before.

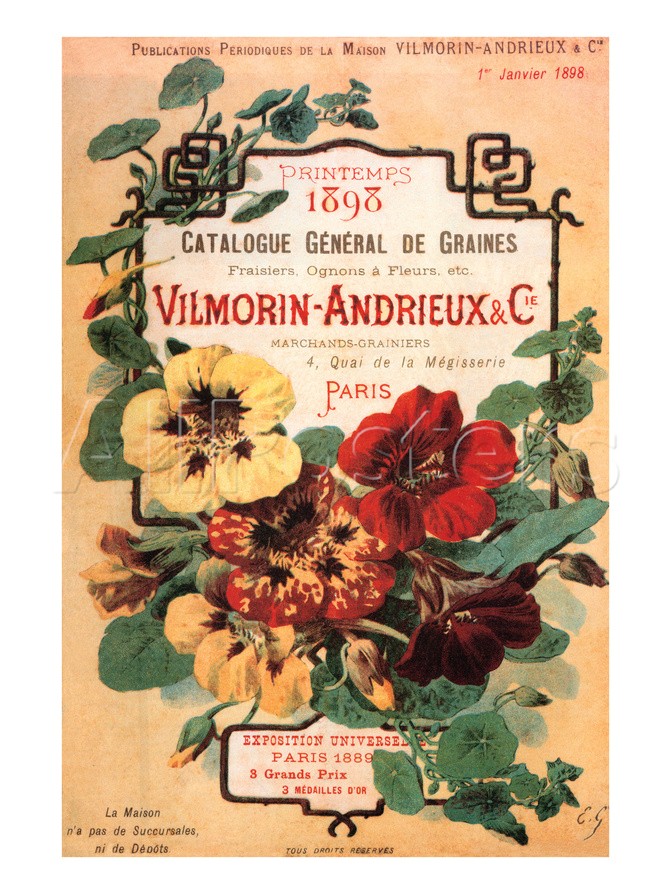

Peter saved the day in the morning when he said, “Robin, just tell stories.” So I shoved the speech in my back pocket for luck, and started talking about our beginnings as potato, carrot and raspberry farmers up in the high country during the drought (2001-2003) (photo of our first farm above). We were very lucky to have the support of some beautiful farmers who spent time “teaching” us how to grow and market our produce. The farm was a commercial farm and although we tried to not conform to the spray schedule recommended to us, in the end, we could actually see why commercial farmers do spray pesticides and herbicides. In monoculture farming, the ecological system in place to assist nature in restoring balance is severely hindered. We simply could not work hard enough to keep up with weeds and the pest infestations ruining the crops. And so we went through the season, spraying and questioning and researching the sprays and being generally horrified by what WE were putting on the food we were growing and going to eat. When we were told that the market price was high for potatoes and we should spray our plants with ‘Round-Up’ to kill the tops making the potatoes ready to sell, we thought…commercial farmers are the ones who should be regulated and jump through stringent hoops so that their food is certified safe to consume! We choose to wait until the plant died back on its own.

We were really lucky that it was a drought year and we had a ready supply of water. We did not have to go through the disappointment and financial down fall of growing a crop through its season only to find that the market price did not warrant harvesting the food! Many farmers face that dilemma and they choose to cut their losses early and till the whole crop in.

I told many more stories but, as I was the one talking, I really do not remember how they all wove together. By the time I finished, though, there were many people gathered and great conversation ensued about the different ways the community could engage more farmers and the regulations which currently restrict buying local food. Here is the rest of my research though…and if you get bored, just jump down to the last three paragraphs where I give thanks…and not just for reading my speech…

*********

The industrialization of agriculture followed the industrial revolution. From highly automated machinery, pesticides and chemically derived fertilizers, hybrid seeds and more recently genetically engineered organisms, food production has the characteristics of other industrial systems. These changes raise a diverse range of social, environmental and ethical concerns about the future of food systems.

To name a few: farmers have been struggling to produce their food for a profit because in order to produce more food they require more off farm inputs, their soil productivity is decreasing, they require more machinery to plant, maintain and harvest the “more” food, which requires growing even more food to pay their rising debt. It is a treadmill of industrialization.

In order to use this big machinery, farmers have had to limit their crops to machine friendly monocultures and to homogenise their farmlands by cutting down trees, ripping up hedgerows, laser leveling the soil …essentially ignoring the specific characteristics of each field and completely limiting the food diversity available to the whole ecosystem.

We have gone from being community members to consumers, a group subjected to brand marketing, price wars and the control of our food by global corporations. The varieties of vegetables that can withstand the mechanization of planting and harvesting, have the “right” genes (to be hardy to grow in a monoculture) and have a long storage life (as it takes awhile to get the food from the field to the “consumer”). They not only contain only the hint of the taste of what that vegetable used to taste like, it also has been subjected to a barrage of chemicals and possibly genetic engineering which we ingest. Health concerns such as cancer, attention deficit disorders, food allergies, and Parkinson’s disease, to name a few, have been linked to the chemicals found on “fresh” produce.

Nutrition is a complex science, moving beyond just what nutrients food contains to the process our bodies do to absorb these nutrients. Some schools of thought within natural medicine hold that the well-being of a plant directly influences the health-giving effects of its fruit. One thing that can be shown clearly through scientific testing is that the levels of vitamins and minerals in fruit and vegetables can vary dramatically depending on the environmental conditions under which they are grown. A famous study from the United States found that tomatoes grown in an area with soil rich in organic matter consistently had levels of some nutrients up to ten times higher than those grown in another area with poorer soil and higher fertilizer use.

I optimistically think most of us would like to be able to choose to eat fresh organic produce, grown by farmers who are doing their best to look after the soil, the air and the water resources available to them and farming with ecologically sound practices. And we think we are supporting those farmers when we BUY ORGANIC. Unfortunately though, with the rapid rise of the organic food market, the historical roots of the organic agricultural movement have transformed into the organic industry. Local farmers have been joined by “new” players – supermarkets, governmental departments and food processors to name a few. The supermarkets are a great example of the social and ecological imbalance of the organic market. Supermarkets are very good at creating price wars which cheat farmers out of a fair wage for their efforts. And when the product is sold, it can be trucked thousands of kilometers to its final destination only to be packaged in plastic and styrofoam, labeled and shelved. It may say organic but the food miles have not only taken away any freshness and created a false sense of “seasonality” it has also left a product which is far from environmentally friendly.

In response to an increasingly globalised food system, and the corresponding social, environmental and health problems which it poses, communities around the world have been developing a different vision for food production and distribution. Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) is a concept which encourages local, environmentally sustainable food production, and which supports both farmers and the people eating their food alike. The CSA concept originated in Switzerland and Japan where people interested in safe food and farmers seeking stable markets for their crops joined together in economic partnerships. Called “teikei” in Japan, it translates to “food with the farmers face on it”.

CSA is a partnership of mutual commitment between a farm (producer) and a community of supporters which provides a direct social and economic link between the production and consumption of food. CSA members make a commitment to support the farm throughout the season, and assume the costs, risks and bounty of growing food along with the farmer. Members help pay for the seed, equipment, labour and other costs. In return, the farm provides, to the best of its ability, a healthy supply of seasonal produce throughout the growing season.

We are very lucky because here on the Peninsula there are many sustainable farmers selling their products in various ways: farm gate sales, farmer’s markets, on-line delivery services and CSA’s. We also have an amazing diversity within small distances which offer us a huge range of produce available, a great growing climate and good soil. We, as a broad community, have the chance to support these local growers by buying local.

***********

And with the speech well received, I returned to our farm to get ready for our first Open Day, a chance for CSA members to see their food growing and meet the people growing it for them. And a chance for us to meet the people who will be eating the food. With our packing shed clad just three days before, I sat in the shade, looking out over the new land, waiting for people to arrive and watched as a whistling kite was chased off by a magpie lark. Even though we have much work to do on the new land, it is already a thriving ecosystem…and it was nice to look out and see all the food growing.

The open day was great. CSA members, friends and family toured the farm. They enjoyed seeing the new land and packing shed and the old land and hearing the story about creating and re-awakening agricultural land, trying to jump start an ecologically balanced system and the triumphs and learning experiences of farming. We talked about biodynamics, pigs and couch grass. And I slowed down from a mad spring frenzy of working to see all of the food growing and feel so very thankful to the earth and the sun and the rain, for all of their help in making that food grow, and to the wonderful 65 families that we will be feeding this summer, for supporting us as farmers and supporting the concept of community supported agriculture! Thank you!! We feel truly blessed.

There were many ideas generated from the speech about how other farms could start on the Peninsula. We would love to see many more small farms growing and feeding our community as well as home gardeners. We are working to share the knowledge that we are learning about market gardening, home gardening and designing sustainable systems. A few people talked about donating their land to farmers who wanted to grow food. We are participating in a great group called Land Share Australia. In their words,Landshare is for people who:

- Want to grow vegetables but don’t have anywhere to do it

- Have a spare bit of land they’re prepared to share

- Can help in some way – from sharing knowledge and lending tools to helping out on the plot itself

- Support the idea of freeing up more land for growing

- Are already growing and want to join in the community